On Institutional Memory and the Role of the Archivist

Since starting this project in October 2015, I’ve been thinking about my role as archivist for the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations (TIHR). I’ve been considering what it means to open up a previously inaccessible archive collection, and the dynamics of bringing the collection out of the storage centre and into the light. I’ve also been thinking about what we mean when we talk about archives and institutional memory, and the role that an archive plays in organisational development and as a form of socio-cultural intervention.

An archive is not just a physical accumulation of stuff stored in boxes on shelves. The TIHR archive is more than the sum of its parts; the 306 boxes that make up the collection provide a visualisation or metaphor for memory and the act of remembering.

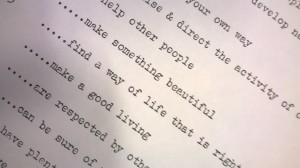

The TIHR archive holds the narrative/s of the organisation and its people dating back to the 1940s. The letters and papers in the archive trace the stories and conversations, debates and dialogues, and ideas and personalities which run throughout the Institute’s history. These provide a microcosm for understanding the history of developments in socio-psychological approaches to the workplace and society in the post-war period.

The archive, made up of these lively interactions and debates, is currently sitting quietly in boxes, just waiting to be uncovered. For me, that is quite an exciting prospect; I don’t yet know what stories and discourses will be revealed as the archive is catalogued and opened up. I’m imagining the sorts of materials I am likely to find, and wondering just what will be discovered in the process.

My training as an archivist leads me to think about archive collections in very practical and technical terms, considering the most efficient and practical ways of cataloguing, describing and arranging collections based on their size, complexity and order. But this project is not exclusively rooted in traditional archival concepts and contexts; but is instead a uniquely dynamic piece of action research, a collaborative project that pools the expertise and perspectives of various stakeholders.

In this sense, this project differs from any I’ve worked on before, presenting new challenges and opportunities and a critical reinterpretation and broadening out of what it means to be an archivist. In this role, I will need to think both critically and reflectively, considering what it means to be located in a co-working cross-boundary environment and to question, analyse and explore different avenues of thought and inquiry. In this sense, the process of working on the project is itself an experiential opportunity, in which I will be considering the dynamics of my role, my relation to the project team, and how the project emerges and develops.

While the project is still in its infancy, I am looking ahead to think about what it will mean to open the collection and make it accessible to researchers. This act of physically making the archive available is a means of bringing the collection into the light. As a concept, the archive offers opportunities for reconceptualising the idea of memory, memory-making, and forgetting; a way of considering how we interact with and re-interpret the past. It acts as a touchstone to the past, a way of re-examining and exploring the development of social sciences over the past seventy years.