Accepting the Constancy of Subjectivity

Niamh Bailey – Student in Fine Art: Sculpture at University of the Arts London

To a student whose work is deeply rooted in ideas surrounding categorisation and dissociation, the archived files of a continuously self-aware organisation proved an engaging read. The following text is an amalgamation of personal reflections from working with The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations’ (TIHR) archive, interspersed with extracted notes from my research in the Rare Materials Room.

Familiarising myself with the archive over a week-long placement was my introduction to the organisation. It was also the first time I spent an extended period with a physical archive. Despite this meaning, I had a lack of experience in primary research of this nature, I believe it assisted my purpose of exploring the archive as an object in its own right. The function of this text is to contextualise and to act as a vessel for abstracts of my notes from the time I spent with TIHR’s archive.

My experiences studying sculpture for the past two years at the University of the Arts London gave me a very specific perspective in my approach to the placement. Upon reviewing the observations and links I’d noted down in response to the archive, it was clear that my artistic practice had been a constant companion as I read. Similarities between my perceived roles of ‘the artist’ and ‘the social scientist’ were recurrent, and I felt a personal connection to the Tavistock’s work, from earlier papers through to their more recent reports.

In response to, Dependence, Interdependence and Counter-Dependence in Residential Institutions for Incurables

By E.J Miller and G.V. Gwynne – SA/TIH/B/1/1/16

It seems as though [TIHR] utilise a system which enables them to act as an outside council and enact helpful structures within an organisation. The focus on systems within their work is something which greatly interests me, as I am keen to understand the relationship between the human mind and the security/productivity which systematic behaviour seems to offer.

I see a similarity between this type of work, and that of an artist. The Tavistock’s work essentially seems to be to utilise their impartiality and general understanding of a sector, to offer guidance and reflection to those who are perhaps in need of it. Although, I would say that the work of the TIHR is most definitely more productive in social change than that of most artists.

A week spent reading through folders was not enough time to make a dent in the archive – I would like to preface any conclusive statements that I proceed to make as being formed in the mind of someone who does not know the work of the TIHR intimately. However, there did seem to be a constant thread woven into the work of the Institute. The idea that there was a Truth or a Purpose that needed to be identified and streamlined by the staff; and, that as an outside agency they were in a suitable position to realise this. It was this which I saw as structuring the work – the hunt and maximisation of the ‘Primary Task’.

The lengths to which the TIHR’s staff went in order to be able to reach the highest standard of objectivity in approaching their jobs was an experience I felt a connection to. I find that a common frustration occurs when past events and preconceptions cloud the vision of a person whose work is to offer others clear and objectively truthful reflection. This is, to a certain extent, the assignment of both social scientists and artists; thus, I found comfort in reading about the efforts of the TIHR in attempting to reach complete objectivity. This sense of reassurance was due to a consistent lack of success in their goal of dissociating from their personal experiences. Despite the programme of group and private therapies that staff members undertook in the founding years of the TIHR, in an effort to detach their thoughts from personal influence, hindsight lends clarity to how social setting and cultural background was still fully capable of skewing the thought processes of the staff.

In response to, Dependence, Interdependence and Counter-Dependence in Residential Institutions for Incurables

By E.J Miller and G.V. Gwynne’ – SA/TIH/B/1/1/16

There is an overriding theme within the paper of assuring that the work of the Tavistock Institute is based in reality. I admire this focus, although I am not sure it is attainable. I believe there to be many different realities, perhaps a reality per person. To truly know reality (as I think the author means it), would be to understand everything, and to be almost god-like in one’s ability to detach oneself from experiences and personal associations. The idea that it is important to stay within the realms of reality essentially expresses to me a concern about the capability of objectivity in humans.

I also question the idea of ‘reality’ itself, in the sense that if we agree that realities are subjective, whilst most sane realities might appear very similar, the pressure to conform one’s experiences and opinions to the socially accepted versions of reality may be a cause for this. ‘Knowing’ the world through the eyes and experiences of a group, and the sense of comfort offered by this perhaps links to the idea that social systems are designed to offer emotional security to adults – essentially extending the nurture and safety commonly experienced in childhood into adulthood.

It is worth noting, that to my knowledge, the TIHR’s archive is untraditional in its structure. It seems to be the case that conventional archival practice intends to guide the hierarchical ordering of papers, so that their structure may reflect the format which the organisation functioned in. The TIHR was founded and run in an exceptionally communal manner, only allocating a CEO in recent years. I was intrigued as to how an archive of this nature would be presented so as not to impose a false sense of structure onto the work of the organisation. Once again, I must admit that a week was never going to be long enough to allow me to come to any meaningful conclusion on this matter; but, I can state that I never felt as though my research was pulled or swayed too heavily when locating materials within the hierarchy. I appreciated the self-conscious nature of the archive and I felt as though the potential influence of the proximity between certain files was well considered.

My work as an artist has deep ties to questions around what shapes and comforts the human condition. The idea of categorisation and structure being a social response, resulting from an emotional need to be mentally and physically ‘held’ is recurrent throughout my physical and written work. Naturally, when noticing the title of Isabel E.P. Menzies’ paper, ‘The Functioning of Social Systems as a Defence against Anxiety’, cited in the bibliography of another paper within the TIHR’s archive, I felt I had to read it. I must be honest and admit that the version of this paper which I resultantly ordered was not from the Tavistock’s archives; although I have since been assured that it can be found within them, I had no such luck!

In response to, The Functioning of Social Systems as a Defence against Anxiety – A Report on a Study of the Nursing Service of a General Hospital, By Isabel E.P. Menzies – PP/LOW/ZA/2/1

“Defensive Techniques in the Nursing Service – Page 9

‘The needs of the members of the organisation to use it in the struggle against anxiety leads to the development of socially structured defence mechanisms, which appear as elements in the structure, culture, and mode of functioning of the organisation. An important aspect of such socially structured defence mechanisms is an attempt by individuals to externalise and give substance in objective reality to their characteristic psychic defence mechanisms. A social defence system develops over time as the result of collusive interaction and agreement, often unconscious, between members of the organisation as to what form it shall take.’”

This text speaks to the idea that categorisation and depersonalisation is a form of anxiety management. I’ve looked into this previously in terms of binaries and polarities within language and a need I have noticed for humans to understand the world through categorisation. It’s interesting to hear Menzies speak on the subject as a trained psychologist as opposed to an artist or philosopher. She suggests that categories act as a barrier between the nurses and the patients, thus allowing the two parties to communicate without the intimacy of their interactions impacting their relationship. This is both a physical barrier in terms of nurses only tending to certain tasks rather than specific patients – and also as a mental barrier, by referring to patients in terms of their medical conditions as opposed to by name. (I am unsure if this is still common protocol in the current NHS.)

I was intrigued by approaching the archive as a reflection of basic human nature – the necessity of organising information and objects as a means of making visual sense of them, as well as to assist others in their understanding. I concluded the week with a conversation with Juliet Scott, the TIHR’s Artist in Residence. We discussed which papers I had been drawn to, what had struck me about the history of the organisation’s work, and what about the experience might lead into her current ‘Object Relations’ work. Our conversation struck upon a point when it became clear that despite my best efforts to read from a broad selection of files, I had drifted towards many of the same papers that others had.

We concluded it was likely that how the archive was utilised is heavily influenced by research trends – examples of these as I write might be feminism, the NHS, and climate change – however, in a decade these will likely be entirely different, and thus the purpose of the archive would be transformed. The issue lies in whether the organisation of the archive reflects the research trends and the personal influences of the archivist at the time of its curation. I am aware that we are circling back to the inescapable idea of the fallacy of objectivity again, and sadly, I have no answers for how the problematic influences of the human mind can be avoided in this line of work. I would recommend to any person that is interested in the work of the TIHR, social scientists, or post-war Britain (to name but a few subjects), to spend some time in the archive. It has proven to be a beautiful wealth of information, and I can confirm that my artistic practice has been greatly fed by the experience.

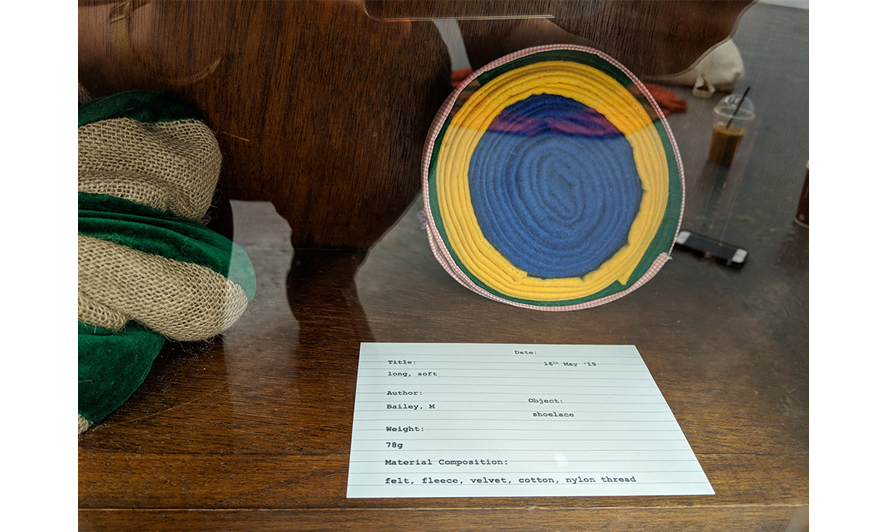

Image credit: ‘Collection no.1’, 2019, Niamh Baile

Wooden & Glass Cabinet, Felt, Hessian, Cotton, Gravel, Polyester Wadding, Thread, Ink, Paper

[…] Source URL […]