Stepping into Practice

Joining the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations (TIHR) as a Researcher and Consultant in July 2015 was for me an exciting step into a more immediate social science practice. Having developed a career in academic anthropology and museology over the previous decade, this was not an incremental step but something far more transformative. Transformative processes are challenging, both for the person undergoing the step change and for the receiving organisation. It was therefore a welcome revelation for me to join the TIHR archive project and, by engaging with some of the archive’s material, to encounter something I could identify with in the Institute’s very beginnings. What I want to convey in this blog article is how this process of engaging with Eric Miller’s papers transformed my experience of my own recent journey out of academia and into practice, into both a reflection of, and a reflection upon, Miller’s similar path some seventy or so years ago.

My first foray into the TIHR archive came through the opportunity to research and present on the topic of ‘Anthropological Threads in the TIHR Archive’ with Dr Sadie King and Dr Mannie Sher ). Sadie, Mannie and I worked together in a Study Room at the Wellcome Library for a few days during the summer of 2016. Whilst we each looked at separate areas of the archive and the Institute’s history, we continually shared our discoveries, our reactions and our feelings as we were able to talk openly amongst ourselves in the Study Room space. This was quite a different experience to the usual solitary silent work one typically conducts when researching an archive in a ‘Rare Materials’ room. The gloves were off, so to speak.

We reflected on our shared experience of training in social anthropology, and its place in our respective career paths. I was looking at field-notes written by Eric Miller which described the clustering of people into different ethnic and socio-economic groups, all of whom worked for textile mills in different parts of the world. Mannie invited Olya Khaleelee to join us, a colleague of Eric’s and later his wife. Olya described her life and work with the Tavistock and with Eric. She then invited me to her home, and together we sifted through Eric’s papers.

An archive is only ever a fragment of a person’s life, and this important work with Olya put this archival fragment into a richer biographical context. It was also the moment at which my own feeling of fragmentation – of a sudden and quite dramatic career change – shifted to something more grounded. I could see in Eric’s early career, as he moved from Doctoral candidate, to Post-Doctoral academic staff, to a consultant-anthropologist within a global textile manufacturing company, and finally to an anthropologist-consultant at the TIHR, something of my own recent transition. I felt moved by Olya’s warmth, openness and generosity and her obvious emotion. We were resurfacing papers and recordings untouched for many years, and I was very fortunate to be privy to this.

So then what?

The material Olya shared with me framed the material that I’d uncovered in archive. Things that hadn’t made sense came together. Fragments aligned. I rushed home to rewrite my paper (it would have been quite different and likely rather erroneous in places without this timely revelation) with only a day to go until our presentation.

So why does this matter?

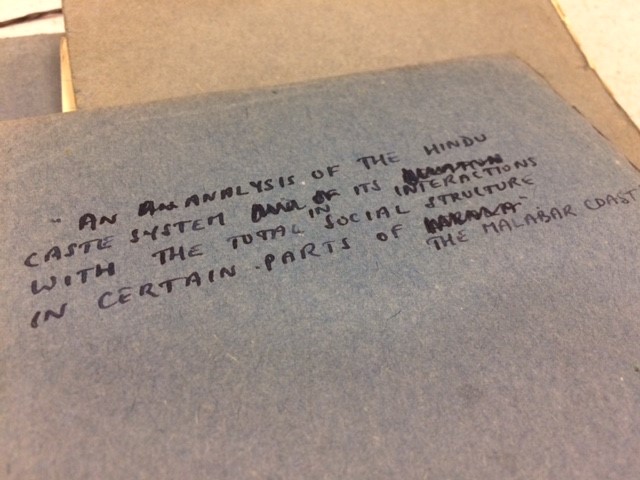

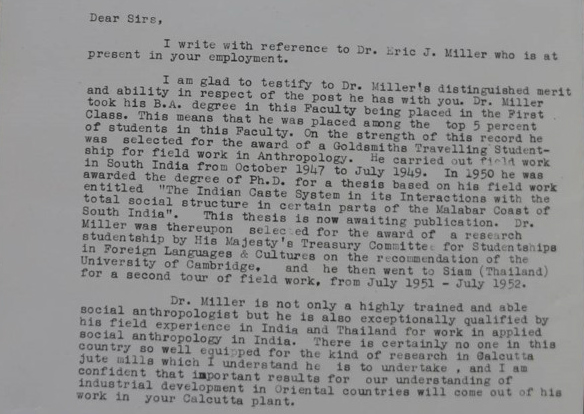

I would like to venture a rather bold suggestion that anthropology – which by and large as it is now practised is purely an academic anthropology – is in trouble. Admittedly, this is not necessarily all of its own making, but I would venture that it’s fair to say there’s an element of collusion in what seems to me to be an overly inward looking academicisation of the subject. How great my surprise to find in the organisational archive of my present employer someone who, with a PhD and Post-Doctoral Fellowship in hand from the University of Cambridge, did not take up tenure but rather walked straight into a full-time consultancy role for a global textile manufacturer in the 1950s; and, more to the point, that his academic research (a study of caste and territory in Malabar, India, published in part here, was considered hugely relevant to this commercial endeavour. And yet, this arguably significant figure in the history of anthropology – a contemporary of Sir Edmund Leach whose name would I expect probably be familiar to every undergraduate student in social anthropology at Cambridge and beyond – remains, to my knowledge, largely unheard of in the discipline as it is currently taught (and I taught it for over ten years).

Why is this? And should we not be surprised, or even alarmed, by the surprise?

As social anthropology grapples with an uncertain future (in levels of funding and numbers of permanent academic positions on offer, for instance), thinking about how better to equip its graduates to step into broader practice (which would at the same time be to increase the breadth, relevance and, dare I say it, impact of anthropology as a whole) seems paramount. How pertinent then that an archive which contains much documentation of anthropology’s relevance and application beyond academia, and which suggests ways in which an anthropological approach to business consultancy might realistically be developed in commercial practice today, is publically available at the Wellcome Library.

Eric Miller and his colleagues established a way of working and engaging with groups and organisations that, as David Armstrong elucidated in his recent lunchtime talk, was given institutional form in the creation of the Tavistock Institute some 70 years ago. Anthropology was a founding ‘thread’ within this Tavistock professional inheritance, and yet this remains little known in the domain of academic social anthropology. Given the social and organisational challenges that anthropology as an academic discipline presently faces, their work could be usefully deployed. Eric Miller is one inspirational example. But there are many others to discover and explore.

With thanks to Sadie King, Mannie Sher, Fiddy Abraham, Shaz Ansari, Ed Simpson and Michael Puett for inspirational conversations about anthropology and its business and organisational application; to Olya Khaleelee for everything she shared; and to myacademic teachers, colleagues and Ngati Whakaue, Tuhourangi Ngati Wahiao and nga iwi o Te Arawa katoa for making me the anthropologist that I am.

The opinions expressed here are my own.